Greying curly hair receding far up his forehead, a short stature made worse by a slight hunch – the result of a spinal deformity – and well-worn clothes, William Cuay was not an overly impressive physical presence. But what this 60-year- old revolutionary lacked, he made up for in charisma, passion and authority as a leader of the Chartist movement. Fighting for the rights of working people in Britain, he was arrested on 16 August 1848 and sentenced to transportation. If the judge at his trial thought this would end Cuay’s political protesting, he was mistaken…

BIRTH OF A REFORMER:

His father, a freed slave from St Kitts, was a cook in the British Royal Navy when Cuay was born in 1788. Little is known about his mother, except that she was English, white and possibly gave birth to her son on a merchant ship in the West Indies. e family settled in Kent, where Cuay trained as a tailor. It was in this trade that he encountered the Chartists, a working-class movement fighting for major political and social reform, which would be laid out in the People’s Charter of 1838. It was Britain’s first mass political movement, and Cuay was at the forefront.

After a strike in 1834 by London tailors insisting on shorter hours and higher pay failed miserably, causing consternation among employers, Cuay lost his job. is, however, only served to radicalize him. He was a founding member of the Metropolitan Tailors’ Charter Association in 1839 and won several Chartist elections in the early 1840s until he became a leader of the London movement. His speeches drew huge crowds and attention, both supportive and critical, from the newspapers.

LONDON CALLING:

On 10 April 1848, the scene was set for Cuay and the Chartists to show their power. A massive demonstration and a march on Parliament were planned – it was time to deliver their petition asking for the vote. Cuay must have been optimistic to see some 150,000 people clamoring in Kennington Common. By the end of the day, he would be furious.

Although the day passed peacefully, the government was keen to undermine the Chartists. The police presence was increased and Chelsea Pensioners were even sent to the British Museum armed with blunderbusses to prevent looting. The march was stopped at Blackfriars Bridge, so Chartist leaders, rather than use force, delivered the petition themselves in taxis. Thousands, especially Cuay, were left frustrated as their great show of power came to a spluttering, anticlimactic end.

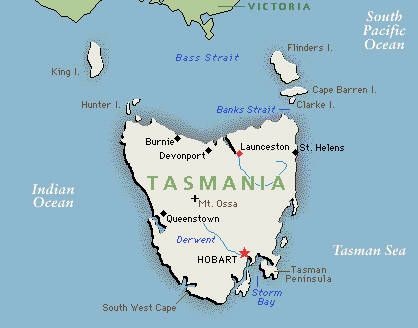

BOUND FOR TASMANIA:

It is possible that this failure pushed Cuay to more extreme measures. When the Orange Tree Plot – a Chartist conspiracy to overthrow the government in an armed uprising – was uncovered later that year, he was implicated and arrested. The evidence against Cuay, and two other Chartists tried with him, came from a government spy.

Accused of intending to “levy a war against the Queen”, Cuay, already 60, was sentenced to 21 years in Tasmania. At the trial’s conclusion, he said, “I have been taunted by the press and it has tried to smother me with ridicule, it has done everything in its power to crush me. I crave no pity. I ask no mercy. I expected to be convicted, and I did not think anything else.” The government finally removed this particularly prickly thorn – The Times once implied he was so influential the Chartists were “the black man and his party,” – from its paw.

LIFE IN THE ANTIPODES:

Having spent 100 days aboard the ship Adelaide, Cuay arrived at Van Diemen’s Land, present-day Tasmania, on 29 November 1849. His wife, Mary Ann, remained in England and all he had was some money collected by Chartist members and a copy of e Poetical Works of Lord Byron, presented to him by the Westminster Chartist Association.

He was a convict in a strange land, separated from his family and in his 60s, but Cuay had no intention of stepping down from political protest. When given a pardon after three years, he decided to stay in Tasmania and Mary Ann joined him in 1853.

He gave speeches, worked on election campaigns and mobilized the working classes, becoming an instrumental figure in Tasmania and Australia. His main causes were abolishing the transportation of criminals, amending the Master and Servant Act to give workers more rights, and fighting to give all men the power to vote.

Cuay was politically active right up until his death at the age of 82, on 29 July 1870 at the Brickfield Invalid Depot. Despite dying in poverty, his authority and reputation meant there were obituaries in newspapers both in Australia and Britain.

WILLIAM CUAY (The Man Who Waged War Agaist The Queen / Leader Of Social Reforms and Political Activist)

Posted on at